|

What did Jesus mean when he prayed, "Our Father. . ."? Find out in my latest contribution to Seedbed's Seven Minute Seminary series (this has actually been up for a few months, but I have been forgetting to post it.

0 Comments

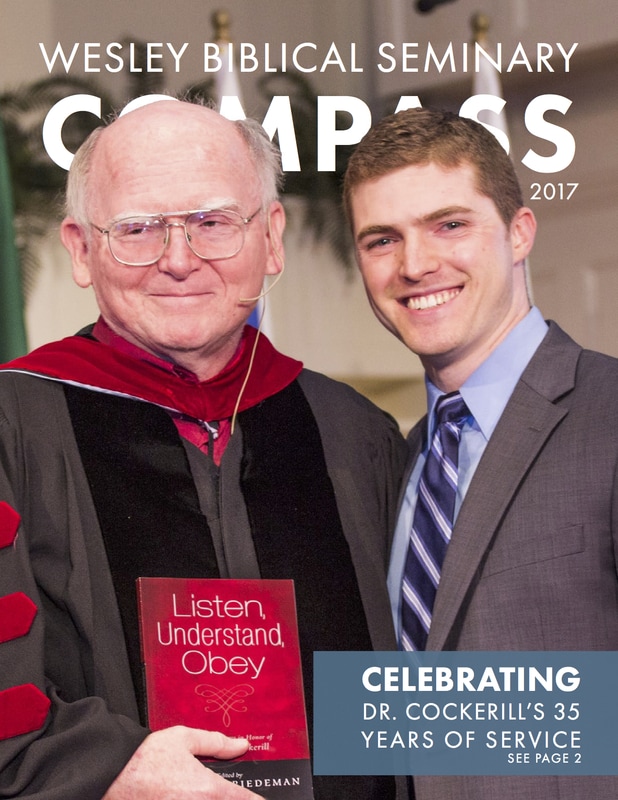

Just received my copy of the Wesley Biblical Seminary Compass last week and was delighted to see Dr. Cockerill, myself, and Listen, Understand, Obey featured on the cover in honor of Dr. Cockerill's 35 years of service. (For the full issue, see here.)

As many of you know, I recently edited a volume of essays in honor of my former professor Dr. Gary Cockerill entitled Listen, Understand, Obey (Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2017; see here for a blog on the volume). This book has been in the works for over two years now, and over that time I have learned an incredible amount about editing. So, although I am far from an expert editor, I thought I would share a few of the lessons I’ve learned in a series of blogs. I’ll present my insights in what I turned out to be the four major stages of the process: proposal, preparation, initial editing, and final editing. If you are editing or considering editing a book, hopefully these thoughts will make your journey a bit easier. Since the book I edited was a Festschrift, I’ll speak to some of the unique issues that Festschriften entail, but most of the points should be transferrable to other sorts of projects. The proposal stage is where you determine the focus of the project, gather the contributors, and pitch the book to a publisher. It helps to do things in that order, because it will give you a better chance at getting the volume accepted by a publisher. Start early The publishing process can take quite a while, so you will want to start the process as early as possible. Obviously, a lot of this depends on the publisher and how full their queue is, but for most Festschriften, you should probably start assembling contributors and pitching the book to a publisher no less than 2–3 years from when you want it to come out. The publisher will probably need at least a year (if not more) with the complete manuscript before you’ll have a copy in your hands. Create a unified focus for the volume Depending on the stature of the honoree, some publishers may accept a Festschrift without a unified focus. However, publishers are generally going to be more interested in a volume with a unified and reasonably narrow focus because this makes it more marketable. In my case, when I originally pitched Listen, Understand, Obey to Pickwick, most of the essays were on Hebrews—Dr. Cockerill’s scholarly focus—but a few were on other topics that he was interested in like biblical theology, hermeneutics, etc. Pickwick accepted it, but asked that we focus all of the essays on Hebrews. You may even want to check with some potential publishers up front to see what sorts of topics they would be most interested in. Another benefit of determining the focus up front is that it allows you to be more specific when gathering contributors. Think through contributors thoroughly Whether you’re publishing a Festschrift or another kind of book, you want to make sure that you get everyone on board who needs to be there, ideally from the outset. For a Festschrift, this is especially important because you don’t want to leave out key people who should have a chance to commemorate the honoree in this way. I would suggest considering in detail the following categories of people: the honoree’s (1) scholarly co-laborers, (2) faculty colleagues, (3) former students, and (4) long-time academic friends who don’t fall into one of the other categories. You will probably also want to run your list by a few people who know the honoree as well or better than you do for brainstorming help. The last thing you want is to wake up in a cold sweat two months before the book releases realizing that you left out someone important. For other sorts of volumes, you may want to think about diversity of perspectives, various aspects of the subject, etc. Finally, you will want to have at least a few well-known names signed on to the project because this will make it more appealing to publishers. Err on the side of too many contributors Reality check: Not every contributor who signs on will come through. This can happen for any number of reasons: illness, technology issues, time management, etc. I originally had 13 contributors signed on for Listen, Understand, Obey and ended up sending 10 essays to the publisher. This was by no means a crippling issue, but at various points (like when I thought I might be losing 4 essays instead of just 3), I worried about the length of the volume. Don’t let this stress you out; instead, plan for it. Tell yourself up front, “Self, several contributors will not come through,” and recruit more than you think you need. Then, when a few contributors email you saying they won’t be able to complete their essays, apologizing profusely, you will smile to yourself and say, “I planned for this.” If you do this, the worst case scenario is that all of the essays come in looking good and you have an exceptionally fulsome volume. Obtain topics and titles as early as possible You may not need essay topics and titles to pitch the volume to publishers, but it definitely won’t hurt you. In addition, having these set early will help you make sure that multiple contributors don’t write on the same subject. Be clear with the publisher on timeline If you have a set date on which you want to present the Festschrift (i.e., retirement, birthday, etc.) or other book (i.e., conference, important event, etc.), you will want to make that clear to the publisher early—probably even in the proposal process. Then, determine how much time the publisher needs with the complete manuscript before you will have a copy in your hands. There is often some flexibility and uncertainty on this point, but the publisher should be able to give you a due date for the complete manuscript that will definitely allow them to hit your release date. For instance, I knew I wanted to present the volume to Dr. Cockerill in early May 2017, and Pickwick told me they could hit that date with time to spare if I gave them the complete manuscript by April 1, 2016. This is important because it will help you make sure that the book appears when you want it to. If you've edited a book before, are there any tips on the proposal stage you would add to these?  I am thrilled to announce the publication of a collection of essays in honor of Dr. Gary Cockerill on the occasion of his retirement. The volume, edited by yours truly, is entitled Listen, Understand, Obey: Essays on Hebrews in Honor of Gareth Lee Cockerill. Dr. Cockerill was my NT professor at Wesley Biblical Seminary and was instrumental in my decision to pursue PhD work, so it has been my privilege to edit and contribute to this book in his honor. Cockerill students will recognize the phrase "Listen, Understand, Obey" as one of the anthems of Dr. Cockerill's teaching. As I say in my introduction, "For Dr. Cockerill, this phrase expressed a deeply-held conviction that the true goal of biblical interpretation is to live the text rather than to merely understand it. . . . The emphasis on hearing God's word is, of course, a product of his lifelong love for the book of Hebrews, which—somewhat uniquely in the NT canon—characterizes OT Scripture as divine speech" (xiii-xiv). All of the essays in the volume treat some aspect of Hebrews, which has been the focus of Dr. Cockerill's scholarly work for over 40 years. His interest in Hebrews began in his doctoral dissertation and culminated in his The Epistle to the Hebrews (2012) in the New International Commentary on the New Testament Series. This commentary replaced one by the renowned NT scholar F. F. Bruce, and Grant Osborne says in his blurb on the back of Listen, Understand, Obey that Dr. Cockerill's commentary on Hebrews is "among the top three ever written." You can view the contributor list and table of contents in the excerpt below, but here is a list of the contributors:

Here is what some senior scholars have to say about the volume:

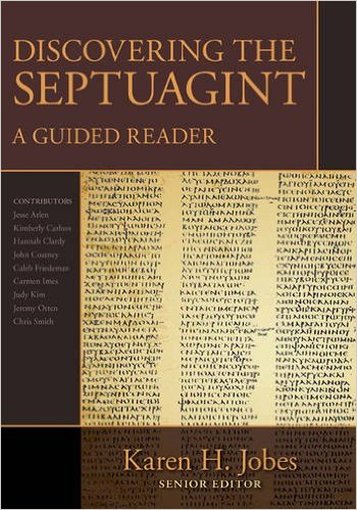

Here is an excerpt of the volume (used with permission of Wipf and Stock Publishers). You can order a copy from the publisher or from Amazon. Last week when I was down in KY I had the opportunity to shoot a few Seven Minute Seminary videos with Seedbed. The first one, "Christians Should Read the Apocrypha," just went live this week—you can check it out on the Seedbed page or watch below:  Motivation is a complicated thing. Some of us have more than our fair share; others could stand to borrow a little. "Be more motivated," we say. But how? A few weeks ago, I was talking with a grad student friend who has trouble studying without some external motivator (a class, degree, etc.) to hold their feet to the fire. For the last five years of graduate education, this has not been a huge struggle for me; by God's grace, I really enjoy my work and just have an inner drive to study without anyone cracking the whip. Of course, I get burned out every now and then, but typically I bounce back after a few days off. As a result, I was initially having trouble explaining to my friend what exactly it is that gets me out of bed and to the library day after day. But then a vivid memory popped into my head—a memory of the day I learned the value of preparation. I'll call it the Two Classrooms Story. Almost exactly six years ago I found myself on a plane headed to India. A rising senior at Asbury University, I had received a grant to go and teach Greek and Hebrew at Living Hope Theological College in Tamil Nadu for six weeks. I had never taught before, but had spent the first part of the summer preparing myself and locating resources (a significant issue for theological education overseas). A couple of days after touching down in Chennai, I finally arrived at Living Hope late at night, and the following morning Muto, one of the administrators, took me around to see some of the classes. The first room we walked into was a Greek class. Muto walks up to the instructor and said something, and he began packing up his books, which seemed odd to me. Muto turns to me and says, "Okay, you can teach for about 45 minutes." I didn't have anything with me, so I quickly ran back to my room and grabbed some books. When I got back, I spent 40 minutes or so working over John 1:1 in detail with the students. I remember being surprised at having so much to say about a single verse and being thankful that I had spent so much time studying before I came. After the Greek class, we took a brief break and then went and visited another class where the instructor was teaching on the Psalms. After watching for a few minutes, he looks up and says to me "Okay, you can teach for 5 minutes." Now, I had read the Psalms many times before. But reading the Psalms and lecturing on them are very different things. Nevertheless, when duty calls you can't really say, "No, thanks." So, I got up and tried to act like I knew more than I did about Psalm 91 for a few minutes. (If I remember correctly, I scammed an insight from my dad about the correlation between the psalmist's faithfulness and call and God's response in vv. 14–15.) To this day I can still remember the visceral and diametrically opposed feelings I experienced in each of those classrooms: in the first, joy at being able to share something of value with the students; in the second, dread at being called upon to say something without having anything to say. And the difference? Preparation. In the first classroom, I had spent weeks preparing to teach Greek, not to mention the countless hours I had invested in studying the language more generally. As a result, I was confident and had plenty to share even when called upon on short notice. In the second, I had a few scattered insights that refused to coalesce into a coherent thought in the pressure of the moment. What I learned that day was not that I needed to study the Psalms more (although that was probably true as well), but that opportunity often knocks at inopportune times, and in those moments the time you have invested in preparation becomes incredibly valuable. However, to stop here is merely to define an additional source of motivation that happens to be constant—"Prepare! You never know when you'll need it!" However, this can easily result in both burnout (I can't stand being pushed from outside all the time) and disorientation (what do I prepare for?). We therefore need to add another element to the equation: calling. God used my time in India to begin calling me to the vocation of a pastor-theologian. As I taught, preached, and studied over those six weeks, I began sensing that this was something that I was being called to do long-term. God showed me how my particular skills and gifts fit into his larger Kingdom purposes and could be used to build the Church. I accepted the call, and it launched me on the life trajectory that I have been on for the last five years. Calling—that sense of God-given purpose—is what makes all the difference in how I think about my work. Because I have sensed, been affirmed in, and accepted God's call, it is part of me in a very real sense. For this reason, what I learned in those two classrooms about the value of preparation isn’t just an external motivator that pushes me. Rather, it connects to the deeply-held conviction that I am called and results in something that feels more like the pull of being drawn towards something than a shove from behind. I am not a psychologist or the son of a psychologist, but I do know that on a sweltering day in India God reminded me of the value of preparation and began calling me in a very specific way. The last six years have not always been easy and I have had my share of “hear my cry, O LORD” moments, but when I wake up in the morning, I generally do so with a sense of purpose, and I find this to be a great blessing. So how do you find motivation? I don’t think you do, at least not by looking for it. I think you look for a God-given calling, put yourself in situations where you can be used and shown your frailties, and then live into that calling with the realization that every moment of preparation counts and is a blessing. To sense God's calling on your life and at the same time truly realize the value of preparation is to become a person of dedication. What gets you up in the morning?  A couple of weeks ago I posted on why Christians should be reading the Septuagint more. However, even for those who know Greek, the idea of picking up the LXX and beginning to read can be a little daunting. Enter Karen Jobes' Discovering the Septuagint: A Guided Reader, just out from Kregel this month. Discovering the Septuagint is designed to help readers with three or more semesters of Koine Greek begin to engage the LXX. The volume contains over six hundred verses of the LXX chosen from Genesis, Exodus, Deuteronomy, Ruth, Esther, Psalms, Isaiah, Hosea, Jonah, and Malachi. Each section begins with a brief introduction to the Greek version of the biblical book followed by a presentation of the chosen texts. Each passage includes:

One of the really cool elements of this project is that a lot of student input went into both the concept for and creation of the volume. I actually had the privilege of contributing a number of LXX chapters to the book, as did eight other Wheaton students. Dr. Jobes was kind enough to get Kregel to put our names on the cover. Thanks Dr. Jobes! In short, Discovering the Septuagint is a great resource that gives students of NT Greek the tools they need to begin to read the LXX. Dr. Jobes has done all of us a huge service in allowing us to glean from her expertise in the LXX. So, if you have some Koine Greek under your belt and are wanting to dive into the LXX, or are considering teaching a class on the LXX sometime soon, run—do not walk—to your computer (okay, so you're already there) and order a copy. Last week, I posted on why modern "New Testament Christians" need to read the OT more if we want to see Scripture like the first Christians did. This week, I want to talk about the Septuagint—the Greek OT that most of the early Christians would have read—and why those of us who are able need to be reading it today.

(Note: Even if you don't know Greek, keep reading—you will probably learn a few things, and I do give a nod to English-only readers toward the end.) First, a little background: In the 300s B.C., Alexander the Great conquered virtually everything and everyone in the ancient Near East, creating an empire that stretched from Greece to Egypt in the south and northwestern India in the east. Alexander's reign exported Greek culture to the areas he had conquered, and one of the results of this was that Greek became the lingua franca of the ancient world. The Jews were not immune to these changes, and as a result Greek became the first language of many Jews. This created a need for a Greek translation of Israel's Scriptures. Around 250 B.C., a group of Jews translated the Pentateuch into Greek, and the rest of the books of the OT were translated over the next century or two. The product(s) became known as the Septuagint ("seventy," abbreviated LXX), because of the tradition that seventy (or seventy-two) Jewish scholars produced the original translation of the Pentateuch. By the time of the apostles, the Septuagint would have been the version of the OT that most Jews and Christians read, much like the King James Version was the standard Bible for English-speaking Christians for several centuries. For this reason, when the NT authors wrote, they referred to the Greek rather than the Hebrew OT—after all, it was what their audience was reading, and likely what they themselves were familiar with. Some NT authors such as Matthew and Paul may have known and referred to the Hebrew OT on occasion, but many would not have. The LXX continued to be the authoritative OT for the Church for several centuries after the Church's inception, and is still used in Eastern Orthodox churches today. The reason many of us today are not familiar with the LXX is that the Protestant Reformation emphasized the Hebrew OT in an effort to get away from Greek and Latin translations and back to the Hebrew original (ad fontes!). From my admittedly Protestant perspective, this was probably a good move both textually and canonically (as a translation the LXX can be hairy at points, and includes a number of books that the Hebrew OT does not). However, we may have swung the pendulum a little too far . . . In my view, one of the tragedies of Protestant reading of Scripture is that we have almost totally lost the LXX—the OT of the early church. For most OT scholars, the LXX is simply a tool for trying to determine the Hebrew original (i.e., text criticism); for many NT scholars, the LXX is primarily a resource for studying individual words and identifying places where NT authors allude to the OT. However, most of us don't read the LXX as the first Christians did, and we don't teach our students to, either. (Of course, to read the OT in your own language is in a sense to do exactly what the early Christians did as well.) My own experience: I began studying Greek and Hebrew in high school at Wesley Biblical Seminary (you can do that sort of thing when your father is a faculty member). My first exposure to the LXX was in a voluntary reading group with some seminary students led by Dr. Gary Cockerill, in which we read a good portion of the Joseph narrative in Genesis and perhaps a few other things (memory fails me at the moment). In college, I studied ancient languages at Asbury University with an emphasis in biblical languages. However, in four years of studying biblical languages in college, I do not recall ever having to engage the LXX in a substantive way. In a way this is understandable; undergraduate programs have a hard enough time fitting in the essentials. However, I would have gladly traded one of my semesters of classical Greek for a course in the LXX. When I returned to WBS for seminary, I was fortunate enough to be invited into a LXX seminar led by Dr. Cockerill. It was in this seminar that the LXX really captured my imagination and I began to sense the untapped potential it had for NT studies. During my first year at Wheaton, I had the opportunity to assist Dr. Karen Jobes on some LXX projects, and got to sit in on her LXX course as well. In short, I have been blessed with a number of opportunities to study the LXX. However, my experience is not that of most students, and was only possible by God's grace through two professors who each had a special love for the LXX. We simply need to do a better job of working the LXX into our curricula so that more students have such opportunities. My study of the LXX and insights I've gained have made me wonder if we are missing out on a lot of connections between the OT and NT. As I mentioned above, we tend to use the LXX primarily for text-critical work or doing a few word searches here and there. However, the NT authors and their readers didn't write and read with concordances at hand; they simply read the LXX and wrote and interpreted out of that knowledge. A couple months ago, I finally got tired of wondering what it would be like to read the LXX as Scripture as the first Christians did instead of merely using it, so I did something about it. Here's what I did: I divided my daily Bible study time into three parts and spent one-third reading the OT in Hebrew, one-third reading the same passage in the LXX, and one-third reading the NT in Greek. For example, if you were spending one hour on Bible study each day, here's what it might look like:

I've found that by dividing things up this way I can both cover a good bit of text (enough to keep it devotional), but also get the flavor of the original languages. Even though I haven't been as consistent as I would like, in the last couple months I've read 12 chapters of Numbers in Hebrew/LXX, all of Deuteronomy in the LXX, and a good chunk of Acts. I'm sure I'll change it up at some point, but this has worked well for me. The best part of this is the connections that begin to open up between the OT and the NT. Here are some of the insights I have gained:

Now you're probably thinking, "Sure, but I could have found out all of that using Accordance." True, but would you have? The problem with relying on word searches for our knowledge of the LXX is that you have to know which words to search for, and inevitably you have to pass over some for the sake of time. In addition, through-reading the LXX allows you to read the OT in a way similar to how the first Christians. If you don't know Greek, engaging with the LXX is obviously going to be a little harder, but there is still hope. Here are a few suggestions:

I conclude with a quote that biblical scholar Ferdinand Hitzig is supposed to have said to some of his students: "Gentlemen, have you a Septuagint? If not, sell all you have and buy a Septuagint." Technically speaking, I'm a New Testament scholar, but over the last couple of years I've found myself repeating a maxim that goes something like this: "The reason we don't understand the New Testament is because we don't know the Old Testament like the first Christians did."

It actually makes a lot of sense if you think about it. The apostles and earliest Christians didn't have the NT—they were writing it! To be sure, by the early 50s A.D. Paul's letters were probably beginning to circulate among the churches, James may have even been written well before that, and by the mid-60s at least one of the gospels was composed. However, that leaves a significant gap between Acts 2 and the composition (let alone canonization) of the earliest NT documents. So, if you were to walk up to one of the earliest Christians—let's say Ananias—and ask him what his Bible was, he would have probably first looked at you inquisitively and then responded: "The Scriptures!" by which he would have meant what we now call the OT. The Bible of the apostles and the New Testament church was the OT, interpreted through the lens of Christ. For this reason, I find it ironic that many Christians regard the OT as obsolete and discard it in favor of reading the NT. Little do we know that in ignoring the OT we are not only depriving ourselves of two-thirds of God's inspired word; we are also dooming ourselves to misinterpreting the one-third we do read. Let me explain: When the NT authors penned their writings, they did so as people whose minds had been thoroughly steeped in the Scriptures, which for them meant the writings of the OT. They also assumed a certain knowledge of the OT on the part of their audience. Even in NT documents that are clearly pointed at substantially former-Gentile audiences—e.g., Luke-Acts, 1 and 2 Corinthians, and 1 Peter just to name a few—there is an incredible amount of OT woven into the discourse. This suggests that even Christians who came from pagan backgrounds were educated in the OT and likely knew it better than most Christians today. So when we try to read the NT without the OT, it is like trying to watch Act II of Les Misérables without watching Act I. As the curtain opens on Matthew we wonder, "Who are these characters? What is the problem? What is the solution?" and so on and so forth. Although we don't have the necessary knowledge to answer these questions (we didn't see Act I), we have to answer them, so we use our existing categories to do so and since we don't have a box for a seventeen-verse genealogy, Israel being in exile, or any number of other things the NT authors are assuming, we end up thinking these bits are irrelevant and putting the emphasis on what makes sense to us. Consequently, we end up with a view of things that is skewed at best and potentially damaging at worst. To illustrate how the OT can really help make sense of the NT, let me give a few examples from a particularly impenetrable book: Revelation. John's Apocalypse is not exactly known for its reader-friendliness; many a would-be interpreter has been sent running in terror from the dragons and beasts and prostitutes (oh my!) found therein. However, what most readers don't realize is that the vast majority of John's crazed imagery is pulled directly from the pages of the OT, often with a twist or two thrown in:

We could multiply examples, but the point is clear: For the reader who, like John and probably like his original audience, is familiar with the OT, these are familiar biblical images connected with OT contexts that help triangulate their meaning. Now granted, identifying the OT references does not tell us exactly what John meant by employing them, but it gets us a lot further down the hermeneutical road than assuming that apocalyptic locusts are Apache helicopters. The bottom line is this: The OT was the only Bible the first Christians knew, and the NT authors assumed this when composing their inspired writings. To truly be a "New Testament Christian" today means to love and diligently study the OT as Christian Scripture. When we read the whole canon the OT comes alive and the NT comes into focus. Interested but don't know where to start? Here are a couple of ideas for application:

Enjoy! Next week I'll be posting on the Septuagint—the Greek OT that most of the first Christians would have read—and how it's been factoring into my devotions lately. As one surveys the landscape of biblical and theological writing in the last half-century, it is hard to think of a plot of ground whose appearance has changed more than Pauline studies. In the late 1970s, a little movement began that has become known as the "New Perspective" on Paul (henceforth, NP). The NP has given rise to a whole slew of scholarly publications proffering new insights on Paul, as well as an equal number of works qualifying or combatting the NP. In all, literally hundreds (if not thousands) of books, articles, and essays have been published in the last forty years or so, and the ground is still shifting, so to speak.

So what's a preacher to do when Sunday rolls around and the text is from Paul? This was my lot a few weeks back. Here I offer a few thoughts on how to preach Paul in a world where scholars are still arguing about, well, almost everything about the apostle's theology. First, a little background. It all started in 1977 when E. P. Sanders published a book called Paul and Palestinian Judaism. Sanders probably didn't realize it at the time, but his study created a seismic rumble in the scholarly world whose reverberations are still being felt today. In Paul and Palestinian Judaism, Sanders didn't so much argue for a different view of Paul, but a different view of first-century Judaism. In particular, Sanders noticed that the dominant trend in Christian NT scholarship (let's call it the "Old Perspective" [OP]) was to view Judaism as a legalistic, works righteousness religion to which Paul provided the antidote. However, as Sanders pored over the Jewish sources themselves, the legalistic Judaism thesis just didn't seem to square with the data. So, Sanders proposed a new paradigm called "covenantal nomism"—the idea that Judaism was essentially a religion of grace based on a covenant relationship with God and that "works" were done as a result of that relationship, not in order to earn it. Sanders' ideas were picked up and developed by others, most notably N. T. Wright and James D. G. Dunn, and resulted in the NP. As NP interpreters are keen to point out, there actually is no such thing as the New Perspective on Paul. In fact, Sanders, Wright, and Dunn themselves disagree on numerous key points (as they have noted in numerous places). Nonetheless, the NP has become an umbrella term to designate a range of perspectives that share certain characteristics. In my view, the following elements at least are central to the NP:

Now for the preaching bit: This year, my church is reading through the entire New Testament together to the tune of six chapters a week. Each Sunday, we preach on the texts from that past week. I don't know why, but when the preaching team was divvying up the preaching dates, I picked the Galatians week. (Those of you who know Paul well will recall that all three of the NP elements noted above come to a head in this epistle.) In contemplating what tack to take, I felt that it would be best to pick a passage that really lay at the heart of the epistle. For me, the obvious candidate was Gal 2:11–21, which, in terms of current scholarly discourse, was a leap from the frying pan into the fire. In the brave new post-NP world, the meaning of virtually every key theological phrase in this passage is contested: "sinners," "justified," "works of the law," "faith in Jesus Christ," etc. Here was my thought process going in:

You can listen to what I did, but here is a brief summary:

In these last two points, I tried to give a nod to what I think are the best insights of both the OP and the NP in Gal 2:11–21. The OP reminds us that we have no hope for justification apart from faith in Christ—neither the works of the Mosaic law nor our own self-justifying strivings will suffice. At the same time, the NP highlights an important ecclesial/sociological dimension of the passage: Those who are justified by faith in Christ are simultaneously unified in Christ—Jew and Gentile, bricklayer and banker, secretary and student. In Christ all the justified are made one. I am an expert on neither Galatians nor preaching. However, as I reflect on my little sermon in the context of all the ink that has been spilled over NP/OP issues over the last 40 years, I can't help but wonder if we could have saved some trees and time by preaching key texts like Gal 2:11–21 a few more times before firing off another book or article. Many of the stark dichotomies between OP and NP seem to dissolve or become irrelevant when one stands before a congregation waiting to hear from God: Justification as soteriological or ecclesiological? Both. Legalism or ethnocentrism? Neither. Faith in Jesus or the faithfulness of Jesus? Yes, both/and, hallelujah and amen! Of course, none of this is to undermine the need for serious theological discourse beyond the pulpit. The Church will always need pastors and it will always need theologians. However, perhaps the Church's theologians will serve her best when they have refined their ideas in the fire of preaching. What do you think? How have you dealt with New and Old Perspectives on Paul in your preaching? |

Caleb FriedemanDisciple. Pastor. Theologian. Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed